Escaping The Simulation (Kind Of)

Hi, today I want to talk about some musings I’ve had the past couple weeks which all revolve around the metaphor of “the simulation.”

Within our current reality, we can’t escape using digital tools completely … so how can we use them more intentionally?

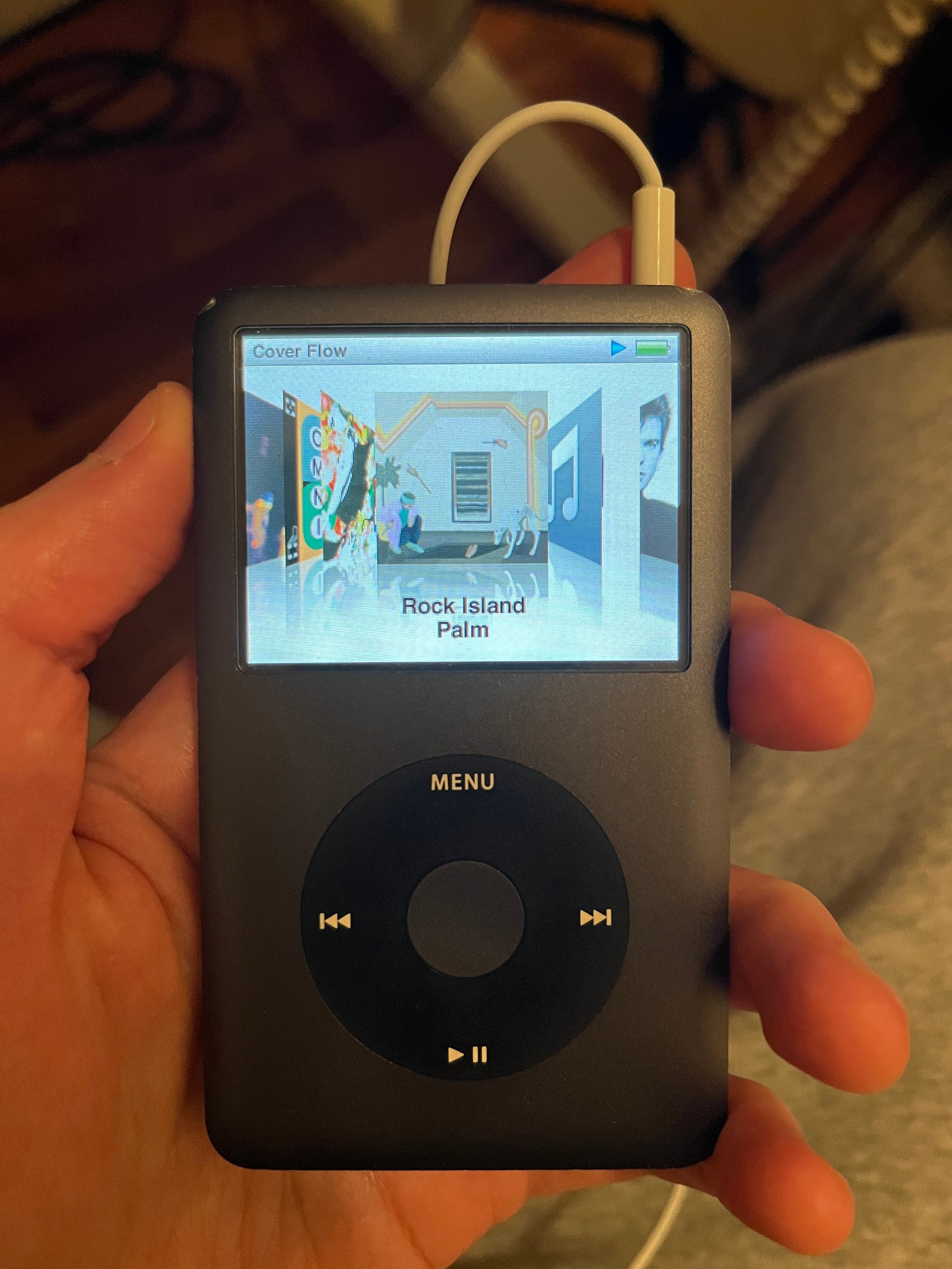

iPods Will Always Be Classic

Last month, I bought a 7th Generation iPod Classic. Yes, they still work. Yes, you still have to use iTunes with them (unless you jailbreak them, which can be done). And yes, they still hold charge (what feels like more than an iPhone, since you only do one thing on it: listen to music.)

This is where the idea of buying one started. I’ve recently been trying to be on my phone less, as many of us are. And I’ve found an app called Blank Space which visually turns your phone into a Light Phone.

This brought attention to the fact that because our smart phones do so much, many times we are never doing just one thing on them at any given time. One is easily distracted, changing from one app to another, while also listening to music or a podcast.

The iPod gets back to the single use device. Not only is the interface more appealing than something like Spotify, but it’s encouraging me to be more intentional with music listening by being a device used for one purpose. On an iPod, never are we bothered by a text or email, never are we tempted to scroll social media.

On top of that, you have to build up its library. This is great because it forces you to actually buy music, supporting artists more directly than what something like Spotify ends up doing monetarily.

It also brings awareness to the idea that none of the music on Spotify is yours. You’re leasing it. At any moment it could go away, if the internet goes down, Spotify goes bankrupt, or an artist takes their music off the platform by choice. An iPod holds YOUR music and yours only.

It’s been a fun 2 months of use since I bought it and I’m excited to see how it changes my listening habits this year. I’ve been finding it to be a beautiful balance between using a fun, convenient digital device, but still holding on to some intentionality and not getting pulled into mindless scrolling.

Amp Simulation Paradox

Apparently a robot conducted an orchestra in South Korea.

I’ve talked to many people working in music about the challenges of recorded music today and one that seems to be really evident is the balance between use of analog and digital tools.

For me and a lot of musicians, the challenge is: how can we make real instruments sound more digital and how can we make digital instruments sound more analog, or real like human instrumentation?

This is most talked about with drums. If you opt to use a drum machine, how can you “humanize” it to make it sound more like a real player? But if you get a real player, how can you make it sound more precise, like a computer? It’s a funny paradox.

For example, there are a lot of electric guitars in one of the scores I’ve been working on recently. However, I’m in a small NYC apartment with an electric guitar but no amp. Even if I did have one…could I be as loud as I need to? Probably not.

What I’ve ended up doing is using Logic Pro’s many digital amplifier simulators. They are actually very good at mimicking the real thing. In fact, this has opened the doors to me putting many different sounds through the amp simulators, not just my guitar playing, leading to fun added texture, and a “realness” to the instrumentation.

That being said, there are some things that the amp simulators can’t really do. There is nothing like guitar feedback from a big Marshall amp and cab by shoving the guitar right next to the amp head. This past week I found that out firsthand after recording at The Warren in Frostburg, MD while visiting my family for my siblings’ spring break.

Much like what we’re facing with questions about Artificial Intelligence, the solution between the digital and analog paradox is likely accepting it and finding an appropriate balance. This is what many musicians do with digital and analog tools, and as much as it’s a struggle, it’s a fun, creative struggle that brings about lovely exploration and discoveries. The obstacle is the way.

Many artists do this now. An artist like Alex G will record real drums but then have those drums trigger samples so that there is a more even sounding performance. A composer like Hans Zimmer will still record an orchestra at Abbey Road, but he’ll layer string samples underneath the recording to beef it up and get the biggest sound possible.

Man and machine can coexist. In fact, they already do.

Temp Music As “Inspiration”

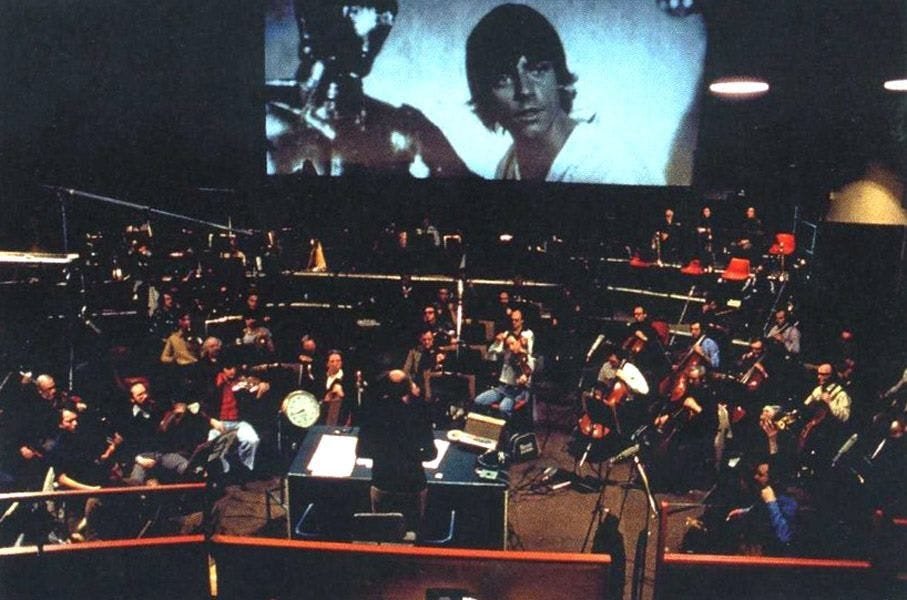

John Williams recording the score for Star Wars in 1977.

Temp music is the music filmmakers will edit to before a score is written, in the event the score isn’t written earlier in the process. It’s preexisting music that, for lack of a better word, fits the “vibe” that the director envisions the score will enact.

As a composer, I’ve struggled contending with temp music. It presents a certain reality of the film, but as the composer, how much of that reality am I to keep, how much am I to let it influence my writing process, how much of the music I end up composing feels original when using temp as inspiration?

It’s something I’d still like to talk to other composers about, and one I’ve begun to do research on myself.

A great podcast I’ve mentioned before on this substack, Settling The Score, had two great episodes which dove into the films’ covered temp music.

For The Incredibles, a score I adore, most of the music is appears to be inspired by John Barry’s work with James Bond. In fact, in the podcast they show that director Brad Bird actually put Barry’s Bond music in an early Incredibles teaser. The podcasters infer that most of the movie was temped with Bond music, going as far as guessing which famous Bond cues inspired which Incredibles cues and playing them side-by-side.

The same goes for AFI’s Best Film Score. John William’s original Star Wars score. In both of these episodes, I was surprised at the closeness between the proposed temp music picks, and the resulting composer’s score. It was fascinating to me.

At first what I felt was a little embarrassing, feeling too influenced by the temp, eventually felt more impressive to me after giving these episodes a listen. Especially in the case of great composers like Williams and Giacchino, the responding cues they wrote often felt better and more inspired than the originals.

The simulated reality of the temp perhaps can’t compare to what these composers end up specially sculpting for films, but undeniably, the temp DNA has influence. Again, we can work with the simulation.

Simulation isn’t always a bad thing. Reality is stranger than fiction. We’re always writing new realities. That’s what do-ing is all about.

will dinola (he/him) is a film composer, musician, and writer currently working in new york city

he is interested in people’s passions and pushing the art of film scoring to new horizons

he writes about his experience in a newsletter called “do”